Anthracnose is now rarely observed in dry and snap bean crops in New York. It has sometimes been noted at low incidence and severity in processing baby lima beans recently (around 2015-2020) but caused by different Colletotrichum spp. (not the highly destructive fungus, C. lindemuthianum).

Anthracnose caused by C. lindemuthianum used to be a major disease of beans, causing serious crop loss in many parts of the world. In 1921, M. F. Barrus of Cornell University demonstrated that anthracnose of bean is seedborne. This information resulted in the widespread use of anthracnose-free seed and a subsequent decline in the occurrence of this disease in the United States. In addition to dry and snap beans (P. vulgaris) and lima bean (P. lunatus L.), scarlet runner bean (P. multiflorus Willd.), mung bean (P. aureus Roxb.), cowpea (Vigna sinensis Savi.), and broad bean (Vicia faba L.) are also susceptible.

Symptoms and Signs

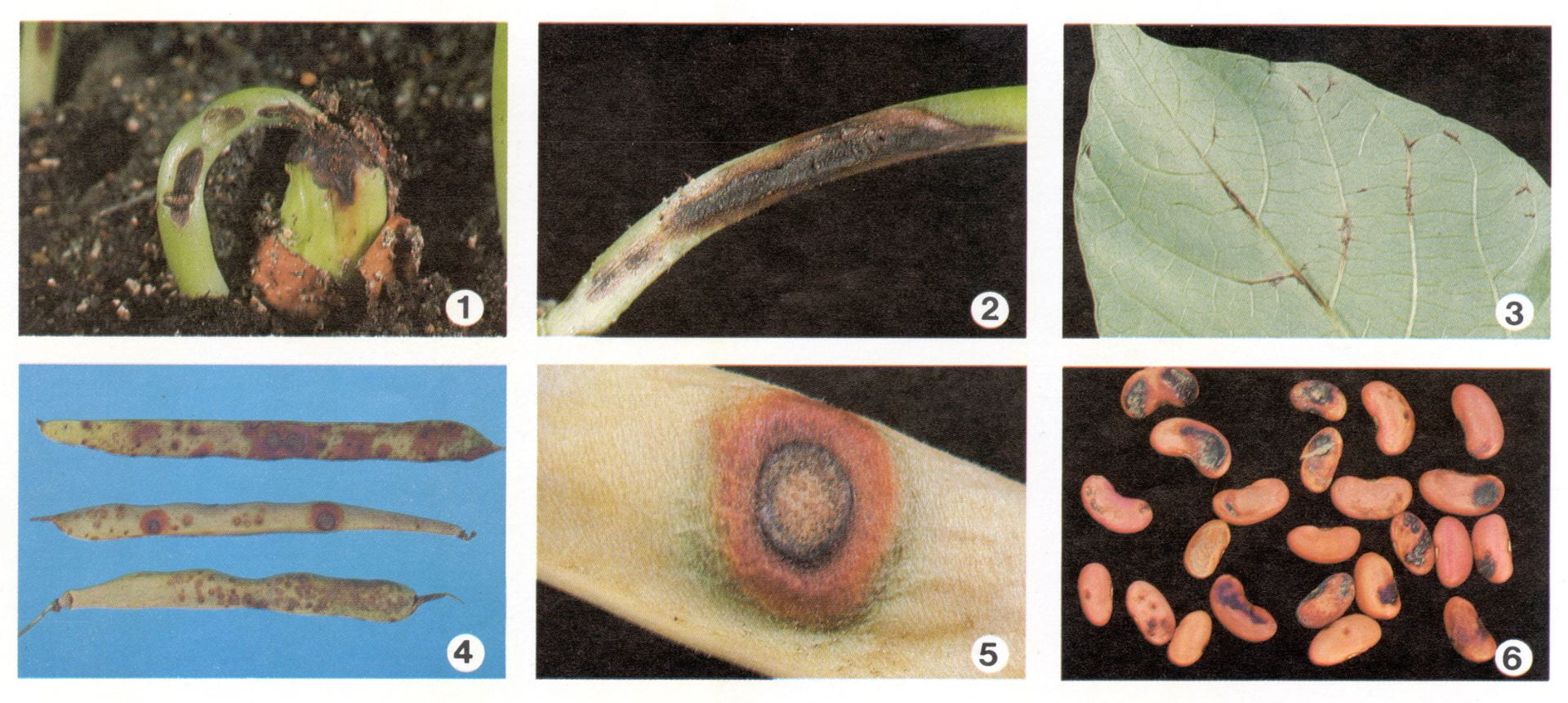

Seedlings grown from infected seeds often have dark brown to black sunken lesions on the cotyledons and stems (Figures 1 and 2 below). Severely infected cotyledons senesce prematurely, and growth of the plants is stunted. Diseased areas may girdle the stem and kill the seedling.

Under moist conditions, small, pink masses of spores are produced in the lesions. Spores produced on cotyledon and stem lesions may spread to the leaves. Symptoms generally occur on the underside of the leaves as linear, dark brick-red to black lesions on the leaf veins (Figure 3). As the disease progresses, the discoloration appears on the upper leaf surface. Leaf symptoms often are not obvious and may be overlooked when examining bean fields.

The most striking symptoms develop on the pods. Small, reddish brown to black blemishes and distinct circular, reddish brown lesions are typical symptoms (Figure 4). Mature lesions are surrounded by a circular, reddish brown to black border with a grayish black interior (Figure 5). During moist periods, the interior of the lesion may exude pink masses of spores. Severely infected pods may shrivel, and the seeds they carry are usually infected. Infected seeds have brown to black blemishes and sunken lesions (Figure 6).

Disease Cycle

The fungus survives the winter primarily in bean seed. Survival in soil or in plant residue varies greatly, depending on environmental conditions. Research conducted in Canada has shown that the fungus can survive 5 years in infected bean pods and seeds that are air-dried and stored at 4° C. Survival is drastically reduced, however, when infected materials are buried in the field and come in contact with water. Laboratory tests have shown that alternating wet-dry cycles in soil reduce survival of the fungus.

Cool to moderate temperatures and prolonged periods of high humidity or free water on the foliage and young pods promote anthracnose development. Moisture is required for development, spread, and germination of the spores as well as for infection of the plant. A prolonged wet period is necessary for the fungus to establish its infection. The time from infection to visible symptoms ranges from 4 to 9 days, depending on the temperature, bean variety, and age of the tissues. The fungal spores are easily carried to healthy plants in wind-blown rain and by people and machinery moving through contaminated fields when the plants are wet. Frequent rainy weather increases disease occurrence and severity.

Management

Cultural practices

Control is best achieved by using anthracnose-free seed. Western-grown, certified seed is highly recommended. Anthracnose development is unlikely on seed produced in semiarid areas, which have little rainfall and high temperatures during the growing season. In contrast, seeds produced in the Northeast are exposed to summer rains and high humidity during the growing season, and the risk of developing anthracnose is increased.

Additional practices to implement where anthracnose has been occurring includes selecting resistant varieties. The use of resistant varieties is complicated by the presence of several forms or races of the fungus, and plants resistant to one race may be susceptible to another Varieties must be tested where they are to be grown to determine their tolerance to the locally prevalent races.

Since the fungus is disseminated in the presence of water, fields should not be entered for cultivation or pesticide applications when the plants are wet. Avoiding unnecessary movement in infested fields will minimize the spread of the disease.

Because the fungus does not survive well under field conditions, infested bean debris should be incorporated in the soil after harvest to reduce winter survival. A two-year crop rotation is highly recommended as insurance against winter survival, and it provides some control of root-rotting organisms.

The fungus survives best on bean seed and to a lesser extent on dried pods and straw. Cleaning and bagging stations in areas where anthracnose has been a problem may be sources of contaminated dust. Thus these stations should be cleaned of debris between shipments and the shipments isolated.

Fungicides

No seed treatments for control of anthracnose on dry beans are registered in New York. The efficacy of seed treatments is variable because deep-seated infections frequently survive the treatment.

Most of the foliar fungicides registered for anthracnose are labeled for use only on dry beans. For labeled fungicides see current Cornell Integrated Crop and Pest Management Guidelines for Commercial Vegetable Production.

More information:

Margaret Tuttle McGrath

Associate Professor

Long Island Horticultural Research and Extension Center (LIHREC)

Plant Pathology and Plant-Microbe Biology Section

School of Integrative Plant Science

College of Agriculture and Life Sciences

Cornell University

mtm3@cornell.edu

Originally prepared for VegetableMD Online website by Helene Dillard. Edited and updated May 2021 by Margaret Tuttle McGrath.