Fusarium yellows, aka Fusarium wilt and more commonly yellows, of cabbage has been known in New York since 1899 when it was found first in the Hudson Valley. It has been detected in all states where cabbage is grown in warm seasons. Yellows is rarely problematic in winter-grown cabbage in southern states except during warm winters. Since 1909 many varieties with high degree of resistance to the fungus have been developed and utilized, resulting in a decrease in occurrence of yellows. There was a period around the 1970s when several European varieties with excellent horticultural characteristics, but no yellows resistance, became popular in western New York. In warm seasons these varieties developed considerable yellows, documenting the value of resistant varieties. Yellows can attack all members of the cabbage family, including cabbage, cauliflower, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, kale, kohlrabi, collards, and radish.

Disease Symptoms

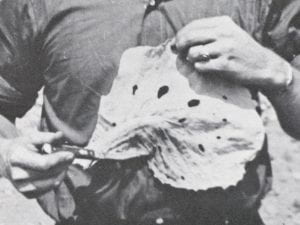

Plants will develop characteristic symptoms 2 to 4 weeks after transplanting, although the disease can appear in the plant bed where it is difficult to detect. The first sign of yellows is a lifeless, yellowish green color overall, but often more noticeable on one side of the plant. A lateral warping or curling of the stem and leaves occurs. The lower part of the leaf blade adjoining the petiole or midrib wilts and dies first, resulting in a curve in the midrib. The lower leaves turn yellow first, and then symptoms move to the upper leaves. With time, the yellow turns brown, and the tissue becomes dry and brittle. The vascular water vessels in the stems and leaves turn dark brown, resembling symptoms of black rot. However, in black rot the dying typically begins in yellow spots at the leaf margins and works downward, in contrast to yellows, which begins internally and appears in the lower portions of the plant first. Also in black rot the leaf veins become black, rather than brown, and are more apt to be discolored than in yellows. The speed of progress of yellows in the plant depends upon the degree of variety susceptibility and the soil temperature. Plants of some varieties growing in 75°-85° F soils may die within 2 weeks. Others may continue to decline throughout the season, die slowly, or even produce a poor head. If soil temperatures decline after infection, the plant may merely lose a few yellow leaves, recover, and make a normal head.

Yellows of cabbage showing curve in midrib.

Causal Fungus

Yellows is caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. conglutinans. Two races have been documented. It is one of several host-specialized formae speciales of F. oxysporum, a worldwide common soil-inhabiting fungus infecting more than 100 plant species that can also opportunistic infect immunocompromised patients. The pathogen produces mycelium, which resembles threads, that grow in the soil and on plant debris. It also has two types of spores, one of which is short-lived, and the other, heavy-walled and capable of withstanding long periods of low temperatures and drought. The yellows pathogen can remain alive in the soil for many years and even increase in soil free of cabbage-family plants. It does poorly at temperatures below 61°F and reaches its maximum growth rate between 80°-90° F. At 95° F it is greatly inhibited. Soil moisture and pH have little impact on the fungus.

Infection and Distribution

The pathogen enters the plant mainly through the young rootlets, although wounds made in older roots at transplanting time may offer entrance pathways also. After penetrating roots, the pathogen grows into the water vessels (xylem), and then progresses up the stem into the leaves. The rate of development depends upon temperature. When tissues die, the pathogen grows through them as mycelium and produces spores on the surface or, rarely, within the water vessels. These spores find their way back into the soil to threaten future crops. Perhaps the principal method of distribution of the fungus from region to region or farm to farm is via infected seedlings or infested soil, clinging to transplants, tractor and farm equipment wheels, and blowing cabbage leaves, or carried in flood waters. Seed plays no role in its distribution.

Control

Since the yellows fungus can live free in the soil for many years and has several other characteristics that differ from most other soil-borne fungal pathogens of vegetables, the conventional control practices such as rotation, seed treatment, fungicide sprays, and destruction of crop refuse are of little value once the fungus has established itself on a farm or in a specific field. Use of resistant varieties is the only control practice. Scientists have demonstrated that 2 types of genetic resistance, A and B, can occur. A type is resistant at all temperatures, whereas B type exhibits resistance only up to 77° F, above which plants will become infected. Fortunately many varieties with excellent horticultural characteristics, a range of maturity dates, and a high degree of A-type genetic resistance are now available. Table 1 lists several resistant cabbage varieties. These should be used for the major crop season with harvest July 15 through November. Very early cabbage generally avoids the disease because of cool soil temperatures.

More information/prepared by:

Originally created for the Vegetable MD Online website by Arden Sherf. Updated May 2021 by:

Margaret Tuttle McGrath

Associate Professor Emeritus

Long Island Horticultural Research and Extension Center (LIHREC)

Plant Pathology and Plant-Microbe Biology Section

School of Integrative Plant Science

College of Agriculture and Life Sciences

Cornell University

mtm3@cornell.edu